Featured

- Get link

- Other Apps

"Punk was like amputating yourself from the culture you grew up in." - Bobby Gillespie and Jim Lambie on Primal Scream, Warhol, William Eggleston and the Rolling Stones

In a white room above the alley where David Bowie posed for the cover of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Bobby Gillespie and Jim Lambie are discussing hair.

“Do you ever get those days,” the artist is saying to the rock’n’roll star, “when your hair is just mental?”

“Yeah, man,” the artist replies. “Washing your hair … washing, it’s just such a pain.”

Gillespie and Lambie first met in the mid-1980s. Lambie was making videos of the bands at Gillespie’s Glasgow club, Splash One and found that using a camera was a good way to meet people. He filmed the first Sonic Youth show in Scotland; the Jesus and Mary Chain (Gillespie was their drummer); and Primal Scream, during an early performance at Edinburgh’s Hoochie Coochie club.

“There was oil wheel lighting on the band,” Lambie recalls. “There was 35 to 60 people there,” Gillespie remembers. “It was a good gig for what we were then.”

For a short time, Lambie played with the Boy Hairdressers, who mutated into Teenage Fanclub. On their gorgeous single ‘Golden Shower’, he plays vibraphone. “I was the worst musician in the world,” Lambie says. “I was technically inept and although I had ideas it just seemed to take forever to turn them into something.”

Instead, Lambie went to Glasgow College of Art, where he studied environmental art.

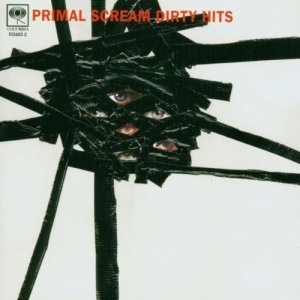

Gillespie followed the evolution of Lambie’s work and asked him to design the sleeve for Primal Scream’s Dirty Hits compilation after an encounter with his taped floor piece at the Tate. “The floor was the size of a cathedral,” Gillespie says, “and he’d lined it with different colours of tape, and it was amazing to walk on it. It was disorienting. I felt as if I was on psychedelics.”

Lambie suggests that he could have built a career on his psychedelic floors, but opted not to repeat himself. His descriptions of his work can sound airy. “Everything’s held together by sound and vibration,” he says. “I see everything bouncing off music. I’m music, you’re music, Bob’s music, everything’s music.”

For Lambie, music and art have always been connected. He heard about the Velvet Underground through reading about Warhol. “I thought, ‘If he likes them and I like him, there’s something I could go and look at.’ So I go out and I discover this amazing band. From that, you listen to what they’re into. That’s what education should be about.”

For Gillespie, the same journey in reverse. For him, music led to an appreciation of art. “And a lot of people got into the Velvet Underground through David Bowie, because he produced Lou Reed and Iggy.”

“That’s probably why we’re doing what we’re doing now,” says Lambie. “Coming from two different areas, and you end up meeting in the middle. Even me using the video camera to hook up with bands, to connect. Warhol’s already there.”

Before designing the Dirty Hits sleeve, Lambie embarked on research, joining Primal Scream for eight days on their summer tour with the Rolling Stones. He flew to Benidorm, then took the bus to Vigo, and on to Lisbon.

“Method artwork!” Gillespie exclaims.

“It was a good learning curve,” Lambie says, laughing. “I learned how to take care of myself.”

The trip, he says, allowed him to get closer to the notion of what Primal Scream are about. The Dirty Hits sleeve is jazzy, psychedelic, punky. “I do freeform all the time. That’s the way to go, man. If I have to plan something, it means I’m outside it. That doesn’t work for me.”

Dirty Hits is drawn from five Primal Scream albums; from their artistic high point, Screamadelica, through their Stones fixation, to their later incarnation as purveyors of brutal electronica.

For Gillespie, ‘best of’ albums were an education. “I had Cannibalism by Can, ’cos Pete Shelley did the sleeve notes. Can were a really weird-sounding band. How can they sound like this and then like that? The same with the Stones. You’d get Rolled Gold and it’d have ‘Under My Thumb’ and ‘Gimme Shelter’ - it made me feel weird that song. I don’t know why, but when I was a kid, it used to really freak me out. It used to put a hex on me. I’d play it in my da’s car, and I’d be like…” He makes a noise of bemused exhilaration.

“Jagger is amazing. How charismatic is the guy? It’s unbelievable. The last night of the tour that we did with them was in a car park at the side of the motorway outside Zaragoza. It was like a George Romero film when we were on. It was raining, there was grey skies.

“The Stones come on, Jagger whipped the place up. He came up into the stage, in the middle, and they did ‘Like a Rolling Stone’. It was frightening. You can tell when people are just doing it cos they’ve got to do it. He was loving it. We had a photo taken before. I looked at the guy and I thought, ‘You’re amazing’. He had a silver jacket on and a beautiful hat.”

Gillespie and Lambie both had a working-class upbringing, Gillespie in Springburn, Lambie in Airdrie.

“Your upbringing and your cultural environment are going to shape your aesthetic and the way you feel about the world,” says Gillespie. “There’s an aggression in our band that, say, the guys in Radiohead don’t have. It’s definitely a need to escape.”

“All I wanted to do was get out of the environment I was in,” says Gillespie. “I wanted to get out of Glasgow. I wanted to travel and I wanted to be in a great rock ’n’ roll band.

“When I was in the Jesus and Mary Chain, I was 22, and that was the first time any of us had left Glasgow. More than anything, I just wanted to try to express myself. I knew I had it in me and I just wanted to do it, but I didn’t know how. This sounds bonkers, but I wanted to make music that I loved and was excited about, and I knew that if I made that music, I could go other places and meet people and do things. Otherwise I would have been stuck living in a room in my da’s house. Nothing against my da, but, you know, I’d been there for a long time.”

“Your initial question about looking out at the world,” says Lambie. “It was more like bringing it in, or drawing it into you. You’d be buying records from New York or wherever. ‘Looking out’ makes it seem as if they’ve got something more. I never saw it as looking out and being dazzled. It’s more like, fuck, this exists, and bringing it in. This is something that I like, and I want that round about me.”

“For me, punk was like a sense of amputating yourself from society or the culture you grew up in,” says Gillespie, “and being encouraged to express yourself. I had already amputated myself, so what gave me the courage to do the things that I did was music, and punk music. This sounds like real teenage angst stuff. It’s not. It’s the fact you don’t want to be a fucking ned. There’s a culture in the west of Scotland - and it’s the same in Manchester or Liverpool or London: that prevailing male, alcoholic, violent, working-class culture - that I don’t want to be part of, that I grew up in. In that culture you’re not encouraged to express yourself. Anybody that tries is put down, so people are scared.”

Punk, Gillespie says, was a means of expressing individuality. “You know when you’re a kid, and you’re just watching things, and you’re taking it in, but you know that you don’t want to do this or that? You go to the football, but you’re not really there. Your body’s there, but your spirit isn’t. You enjoy the match, but not what goes on around it; the violence and the sectarianism. You’re already cutting yourself off. For me, the punk thing was like, ‘At last, some people that think like me. I’m not alone.’”

Punk also encouraged the notion that technical excellence was less important than enthusiasm. “People who indulge in the technical side of it become elitist,” Lambie says. “It’s like Santana as opposed to the Pistols. It’s like maths rock. Most people who heard the Pistols reckoned they could start a band. It’s the same in art. Technically gifted portrait painters - that’s fine, man, but for me it’s more about ideas. Ideas can happen in an instant. Things can come together really quickly. That’s much more of a release, more of a generous act.

“I’ve never had any ambitions other than just making work,” Lambie says. “I’ve never had any inspiration. I’ve only ever felt as if I’m just noticing something that I haven’t noticed before. I wouldn’t put it down to inspiration, because that sounds as if it’s coming from a higher place, and I think, very much, it’s coming from round about me, where I am right now.”

“Maybe you become better at it,” Gillespie says. “When we started out we weren’t that great, but we had something. People used to write that about us, that they liked the spirit, but not the music. If you eventually write the right music, you transcend that and become something else.”

Over lunch in Heddon Street, towards the end of their second Coca-Colas, Gillespie and Lambie talk about the aura that surrounds certain musicians. Johnny Cash, says Gillespie, had a big spirit. “It’s like Hank Williams or Jerry Lee Lewis. They’re just permanent.”

“They’re signs as well,” says Lambie.

“What do you mean?” says Gillespie.

“Signs are everywhere,” says Lambie. “Someone who’s a bit more involved in art, they pick up on them and turn them into music or art. Johnny Cash created a lot of songs that became signs for people. He’s always present. He’s always something for people to go back and look to, and say ‘that was a particular point in time’, or how I felt then. So he becomes a sign of how their life came together.”

“The last time I saw Johnny Cash was about 1989,” says Gillespie. “His band was all dressed in black, and when he came on his voice filled up the whole fuckin’ hall. I’d never heard anything like it. I’d been to hundreds of gigs, but his voice had this weight. It was like a big black cloud. You know when you see a big black storm coming up the Mississippi river? It was like that. It was eternal.”

The talk turns to Memphis, Tennessee, the home of rock ’n’ roll and Southern soul, a city to which Primal Scream have made several pilgrimages. On one trip, to record the Dixie Narco EP, they arranged to meet photographer William Eggleston, with a view to using one of his pictures on the sleeve. At Eggleston’s home, they found the great man in an advanced stage of hospitality.

“He had this really short hair, and this grey army pullover. He had jodhpurs and boots on. He looked like a colonel in the Confederate army. He looked really aristocratic, but in a good way: wild-looking.

“He was walking about with a big rifle with a bayonet. His wife’s lying on the couch in a negligée. It was totally Southern gothic. It was crazy. He sat at the piano. He said, ‘Do y’all like Rabbie Burns? Well, fuck you if you don’t, because I’m going to play some.’”

“Eggleston changed the way I thought about making work,” says Lambie. “The colour had drained out of most contemporary work, and I started looking at his photographs around 1992. The colour saturation was amazing. Look at my work now, there’s always a lot of colour. I remember saying to [Big Star singer] Alex Chilton,‘Eggleston’s photographs changed my life.’ He’s like, ‘I can’t imagine a photograph changing anybody’s life.’ I was like, ‘Lots of things change lots of people’s lives.’”

Gillespie creases up, making the noise of a slowly deflating ego.

“The next time we went to America, I met this lady,” he says. “She was friends with Tom Dowd, the engineer/producer who did a lot of work for Stax and Atlantic, and he did A Love Supreme for Coltrane. He was an amazing guy, and this lady was an old Memphis friend of his. She used to come to the studio every day with really expensive cakes. We called her the Quaalude Queen because she was always bombed. She used to be Elvis’s press agent, and she was going to introduce us to [Elvis’s physician] Dr George Nichopolous’s daughter. Dr Nick’s daughter! We were like, ‘Please, please, anything to get to the great man for a script.’ It would’ve saved my life, but Dowd thought the sessions would’ve fallen apart.

“Anyway, she was friends with Eggleston. She says, ‘You’d be driving a car and he’d go, click, and take a picture of the clouds, and that’s it.’

“People would say to Eggleston, ‘Do you ever see something and wish you’d gone back and taken a photograph of it?’ He says, ‘Aye, but I never go back. You get one chance.’”

Lambie grins through the mist of his mental hair. “That’s it.”

(Interviewed in London W1, October, 2003. A version was published in The Scotsman).

Popular Posts

Phil Kaufman: Executive Nanny, Corpse-Rustler, Road-Mangler Deluxe

- Get link

- Other Apps

Real Sex In All Its Artless Banality - Michael Winterbotton's 9 Songs

- Get link

- Other Apps

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment