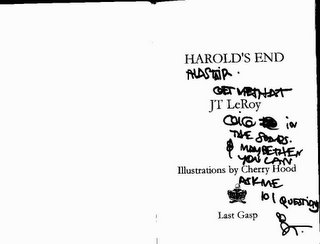

Much has already been written about the literary hoaxer JT Leroy. Here, for the sake of completeness, is an unpublished interview with JT, or the actor who played him, which took place in London in April 2005. At the end of the interview, JT signed a copy of Harold's End with the message: "Get me that gig in the soaps and maybe then you can ask me 101 questions."

A reading by JT Leroy is not a regular event. In spirit and in style it is closer to the kind of gathering that might have congealed around Andy Warhol. A Leroy audience is full of superstars, some of whom are even famous.

As I stood outside the London bookshop where Leroy was due to appear, Samantha Morton walked past and telephoned Bella Freud. At the other side of the door, the actress Margo Stilley – star of the sex drama,

Nine Songs - was adjusting her cap.

For most of the event, Leroy was cocooned in a back room, while invited guests read from his work. His absence was as strong as his presence.

In New York, they got Lou Reed and Shirley Manson. (Manson also wrote the Garbage song

Cherry Lips about him.) In London, there was Nathalie Press, the star of Pawel Pawlikowski’s coming-of-age drama,

My Summer of Love. Harper Simon – son of Paul – claimed to have met Leroy the day before in King’s Cross. “He convinced me to read tonight. Because I thought he was holding.” Beth Orton confessed to being unfamiliar with the books. “I have never read any of his stories, but I got given this today, and I thought to myself: his works are edible.” Most impressively, there was Marianne Faithfull, who ignored the vernacular of Leroy’s stories, and delivered them instead in an aristocratic estuary English.

Then, after much coaxing, there was Leroy; a small, anxious figure, his features hidden beneath a hat, blonde wig and sunglasses. He wore a lucky raccoon penis bone around his neck. When he spoke, it was in a cartoon whisper, somewhere between Mickey Mouse and Michael Jackson. Faced with questions from the floor, he crumpled. There was applause, and a long queue for autographs.

I asked Faithfull why she was interested in Leroy. “Because it’s real writing,” she said. “Really good writing. There’s personal experience, and that’s a place to start, but there’s much more than that. This is real writing.”

And the disguise? The studied enigma?

“He’s a kid,” Faithfull said. “He’s got to create a persona, and to go through all the stuff that we all had to go through. And then shed it all again. But that’s just rubbish really: he’s got to keep writing. And he will. Already I can see with

Harold’s End, and even with

Sarah, it’s moving beyond the autobiographical. I’ve read a lot of these things – I love autobiography – and you know when there’s no more to say. There’s a lot more to say here. The detail, the building of the terror.”

“Thank you,” I said to Marianne Faithfull.

“Thank God the Pope’s dead,” she replied.

Outside, I ran into Hanif Kureishi, who said he had never seen anybody as nervous at a reading. Kureishi had earlier met Leroy at Bella Freud’s house, along with Nick Cave, and found him to be “a very sweet guy. He was perfect company for the kids. He seemed to prefer the company of the kids to the adults.”

And the writing? “The writing’s obviously very good,” Kureishi said, “and there’s something quite extraordinary about it. A mixture of lowlife and very erudite reading.”

What about the disguise?

“I hear that West Virginia’s a pretty rough place, so walking around in that gear is not gonna get you very far on the High Street.”

Before you get to JT Leroy, you have to separate myth and reality. This is not easy: with Leroy, myth is reality. This confusion has led to suggestions that Leroy does not exist, and is a pseudonym for (among others) the writer Dennis Cooper, or the filmmaker Gus Van Zant. Certainly, both encouraged his writing. (Leroy wrote the unused first draft of Van Zant’s Columbine film

Elephant).

Leroy himself has compared the process of becoming “JT Leroy” to putting on a Spiderman outfit, in which case, it seems presumptuous to use the word “facts” to describe his early life. The accepted realities are these: he spent his teenage years being hauled around truckstops of the Southern US by his mother Sarah, a prostitute, and found himself embroiled in a life of drugs and abuse. Sometimes, to help his mother, he would pretend to be a girl, because his mother’s clients were less threatened if they thought he was his mother’s little sister.

He started writing at the suggestion of his therapist , Dr Terrence Owens of the McAuley Institute, San Francisco, and has now published three books;

Sarah,

The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things, and

Harold’s End. All three titles lurk in the uncertain terrain between memoir and fiction.

The Heart is Deceitful has been turned into a movie by the star of

xXx, Asia Argento, who also stars in the film. Leroy claims to have seen it 20 times, and to have learned something new every time. “It’s amazing,” he tells me, with Warholish enthusiasm. “That’s a real true test; if something can withstand being watched that many times, but you still look forward to it and you’re still nervous. It’s like these little details… wow!”

In person, Leroy is less anxious, though his speech still exists on the fringes of audibility. He wears a leather jacket with the sleeves pushed up. The wig is pushed back slightly, revealing short, mousy hair. There are few signs of a beard, and no sideburns. He resembles a boyish girl more than he does a girlish boy.

He emits a forceful sense of disconnection. He is rarely declamatory. I ask about his therapist’s suggestion that he should write about his experiences.

“I couldn’t remember from one session to the next,” Leroy says. “We’d go over the same stuff over and over. I was just clouded. So he wanted, for continuity, to get me to write it down. I’d go into this great detail, and then I couldn’t remember it the next time. He was teaching social workers, training them at the university, so he put a carrot in front of me and said: ‘Why don’t you write, and show the social workers what they need to work on?’ I had bitterness towards the social workers that I had met in the past.”

You thought they had agendas?

“I felt like the system ssssssucks. There’s like these loopholes and these things in the system and they go completely to code. I don’t blame them for it, because that’s how the system’s set up, but he gave me that opportunity: he said these are people who are training to be social workers so you can tell them. So I would write for them. That was what got me hooked.”

With the support of Dr Owens, Leroy discovered his voice. The structure and the vocabulary came later.

“I think that happens when you write more. I would ask [Dr Owens] craft questions, and how to write, and he didn’t know the answers to that. Then I realised … I’ve always been a big reader but I got really into certain writers, and I thought, if they weren’t dead, or even if they were, I could try to contact them. It hadn’t struck me before, so I would try to harass people for writing techniques.”

He contacted Tobias Wolff, Michael Chabon, and the poet Sharon Olds. The best advice he received was from Mary Gaitskell. “Some of the people that I talked to, they were just really sweet, but she took to me with kid gloves. She’d go into gritty detail. Like when something’s a cliché. She taught me to go into it, and pick things apart. She made me look at it in, like the kindling… to see what’s there. You write something and you have to pick it apart.”

At the reading, Leroy was asked whether he would move his writing beyond autobiography. In the absence of a response, the question was answered by Faithfull, who suggested that he had already. Now, Leroy says: “With

Sarah [his second book, though it was published first] I learned how to play more. It’s not so much about survival. It’s really interesting. I think when anybody writes, you can trace it back to something to do with their life or their experiences. You can trace it back to something in their emotional reasoning. Writing is like a frame. And you trace it back.”

We talk for a while about Leroy’s discomfiture during public appearances. He confesses to hating them. “I want to puke.” Why, then, does he do them? “I think I crave attention, but when it comes down to it, I really don’t.”

Fortunately, Leroy has a supportive audience. If anything, his shyness seems to endear him to them. “That’s because it’s so uncomfortable. I get really paranoid. I think people can see…” - he points to his forehead – “in here.”

The disguise, he says, is a way of dealing with his discomfort.

“I feel like I’ve gotten a little bit better. It’s been a very slow thing. I think I had a form of agoraphobia. I couldn’t leave the house. I used to stay … in the dark, really. And when I would talk to people or do interviews I would do really inappropriate things. I used to wear a mask, but it broke.

“But I think it’s better with each time. It’s getting more bearable.”

After a while, of course, the disguise becomes the act, and causes people to speculate about Leroy’s sincerity, which could be a problem for a writer whose work is based on the power of honest revelation.

He laughs quietly at this thought. “Huh huh.”

So you are who you say you are?

He nods.

And you write these books?

He nods again.

And you are male?

He nods again, more uneasily.

I mention something he said a few years ago, about achieving genderlessness.

“Yeah,” he says. “I like all that stuff, like planting all that stuff that I could be” he whispers, “somebody else. I have to remind myself - I get really high-strung, constantly - that’s it’s all play. I’ll try to write with my left hand instead of my right. And I’ll wear all different kinds of disguises. Different identity stuff.

“Some days I’ll wear a different wig, or hold my head in a different way. I like being fluid, and keeping it that way, and trying to change, and making myself try to taste different things and just move, otherwise I end up being in the house for a year, without moving. And I find it helps me. It keeps me present and aware. So.”

Leroy lives in San Francisco with his surrogate family, Emily and Astor, who also play in a band, Thistle, for which he writes the lyrics. Leroy does not perform with them: “No! I’m not ready for that!”

His answers are turning monosyllabic. I ask whether he thinks it is possible to share too much in his books.

“What do you think?” he replies.

I think his trust is ebbing away. We talk about this. Or rather, I talk. Then he brightens and says: “It takes so long!”

To write?

“No. To get the response. You’re wringing your hands and nobody’s read it yet. It’s just sitting on your desk.”

Other things to know about Jeremiah Terminator Leroy:

He would like to write screenplays.

He believes in luck. “I’d say most of what’s happened up to now has been pretty lucky. I’m finally at the point where I maybe should start to take the reins.”

His favourite mistake was: “Buying a dark chocolate bar instead of a milk one. Like, if they offered milk, why wouldn’t you go for it? But with dark, you get more of the drug.”

Finally, I ask this famous chronicler of terrible childhood to tell me his earliest memory. “Hmm,” he murmurs after a long five seconds. After 20, he says quietly, “I don’t want to tell you.”

So, if you have a book signed by an actor pretending to be the author, is it worth more or less than an unsigned copy?

ReplyDelete