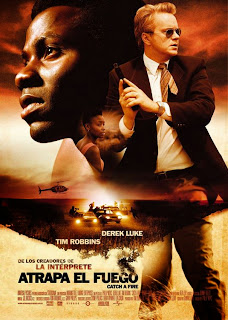

When she visited Cape Town for the opening of her film

Catch A Fire, Shawn Slovo went to the Olympic-size pool at the seafront. In her childhood, it was a whites-only pool, but now, on weekdays, busloads of children travel from the black townships to swim in the saltwater. She watched them clambering to the highest diving board, and plunging fearlessly into the water, screaming with joy. Turning to leave, she saw a black man in his fifties, looking down at the scene.

“He said: ‘When I was a child, I used to come to this place, and all I wanted to do was swim in this pool’. There were heatwaves in the townships, and no trees. And he said: ‘I’ve been coming here all my life, and now I can watch, but I can’t swim.’”

As a writer, Slovo’s use of metaphor is quite precise. The new South Africa is far better, she thinks, but there is still a long way to go before the legacy of apartheid is overcome.

A measure of the country’s progress can be seen in

Catch A Fire, which tells the true story of Patrick Chamusso, an apartheid-era everyman who is wrongly accused of terrorism, and interrogated so brutally that he signs on with the (then illegal) African National Congress to help blow up a power plant. Robyn Slovo, who produced the film, says the comparison with contemporary politics is deliberate. “It’s about how, if you take away people’s basic human rights, you are in danger of creating the very thing that you fear the most.”

Catch A Fire is a sequel of sorts to the more autobiographical

A World Apart, which won Shawn a BAFTA for best original screenplay in 1988. The earlier film told the story of a childhood shared with Robyn and author Gillian Slovo (whose memoir

Every Secret Thing covered the same territory) as the children of the leading anti-apartheid activists Joe Slovo and Ruth First. At his funeral in 1995, Joe Slovo was hailed by Nelson Mandela for his efforts in the ANC as a “great African revolutionary”.

“Both of us have experience of being the children of members of an illegal organisation,” says Robyn, carefully avoiding the word “terrorist”. “And our father was very high up in the armed wing of that organisation.”

Before the banning of the ANC, the Slovo sisters enjoyed a life of regular white privilege. “Private schools, swimming lessons and horse riding; all that stuff.” In the later part of the 1950s, their parents were arrested as part of South Africa’s Treason Trial, so they became more aware of their circumstances. “We really were a very strange and peculiar family as far as the rest of South African society was concerned,” says Robyn. “Because black and white society didn’t mix.”

Joe and Ruth were friendly with Mandela and his ANC mentor Walter Sisulu, so the family sometimes visited the black townships. “Occasionally there were actually black South Africans in our house,” says Robyn, “apart from in the kitchen and the garden and the laundry room. My parents would have multi-racial parties – breaking the law – and were busted a couple of times.

“We knew we had parents who were very unusual and very brave and very committed and who had the greater good in mind. Which is a problem if you’re their child, because the greater good is quite a large thing to be in opposition to.”

“They were great human beings,” says Shawn, “but terrible parents. You can’t parent properly under those conditions. Parenting means spending time with your babies as they are growing up. We never wanted for anything, but we had parents who were activists. Parenting means continuity, and being there to give your children support, and support takes time, and they were off fighting for the rights and freedoms of 35 million black people. Your demands as a relatively-affluent, white middle-class child pale by comparison. It’s not ideal parenting.”

In

A World Apart, Shawn explored the sense of resentment she felt in her early teens at having to share her parents with a cause. “And I must tell you, they didn’t sacrifice anything particularly. By taking the path they took, they felt fulfilled as individuals, and they had a very exciting life. In their twenties, they were living in a John Le Carre novel. Dead letter drops, going underground, leaving a country without a passport. A lot of constructive stuff, a lot of action. They had good friends and a good time. As far as they were concerned they were not sacrificing anything. This was what they wanted to do with their lives.”

When Shawn talks like this, there is a sense that not all of the hurt has healed. The children were left with their grandparents when Ruth was jailed and Joe was stranded in Southern Rhodesia on ANC business. In 1963, the family was exiled to London. “I was just so thrilled that our mother was out of jail, we got her on the plane, to be with Joe in London, and for a brief period we were a proper family,” says Robyn. “We saw TV for the first time. We got here and it was the coldest winter in a hundred years, so the Thames was frozen. Snow everywhere. We’d never seen snow.”

In exile, their father remained optimistic. “Joe always used to say we would be going back to South Africa,” says Shawn. “Since 1948, when people asked ‘how much longer?’, he said ‘five more years’. He said that every year.”

Though they have stayed in London, both Shawn and Robyn consider themselves South African. “There is something about a traumatic leaving and the connection you have through your parents to the country that never goes away,” says Shawn. “Also you come here to Britain in the early Sixties, you are South African. You’ve got a South African accent that is most unbearable, so you’re struggling to lose that, but you always are an outsider.”

Robyn puts a more positive spin on their nationality. “What happened in South Africa completely changed our lives. It’s meaningful to us, and our father went back and was a minister in the Mandela government. We didn’t have an extended family, but those people who would have been our extended family are the Mandelas, the Sisulus, the people we grew up with. They are part of the fabric of South Africa. So we belong to it.”

She mentions something Patrick Chamusso said about how he was encouraged to believe there was hope during apartheid by the fact that Joe Slovo was white. “It allowed the struggle to move beyond black against white. It became people who wanted a democratic free society against those who didn’t – and that’s what prevented it from being rivers of blood.”

The Slovos were not immune from the country’s tragedy. In 1982, Ruth First was killed by a letter bomb sent by the South African security services. “It was a terrible shock,” says Shawn. “It was a call I had been waiting for all my life, but I always thought it would be Joe.”

“The only thing about it is that we understood who had sent the bomb,” says Robyn. “We understood the context; we had been brought up in this way. It doesn’t seem random. In some horrible way, it makes sense that they could do this.”

As part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission their father helped establish, the Slovo sisters sat in a courtroom while their mother’s killers, police spy Craig Williamson and his bomb-making team, appealed for amnesty. They were freed because they claimed the bomb was meant for Joe, a legitimate target - an argument the Slovos dismiss. “That is a very sour aspect because the truth did not come out,” says Shawn, “but it doesn’t make you want to go on a vendetta and get Craig Williamson. If he was seated as close as you are – which he was in the courtroom – and somebody handed me a weapon, there’s no desire for revenge.”

The absence of vengeance is one of the most positive aspects of the new South Africa, and is reflected through Patrick Chamusso’s story in

Catch A Fire. “But,” Shawn concludes, “when Patrick says, ‘If I take revenge then it will be war, generation after generation,’ there is pain in his eyes. It doesn’t mean that you don’t hold the hurt for the whole of your life.”

I wonder how high the diving boards were?

ReplyDelete