Interviews prompt a question about questions. Just as fiction writers are often said to be writing autobiography, interviewers ask questions about themselves. Or - and this is where it gets complicated - they are asking questions about their imagined reader. The most successful newspapers have a very clear idea of who their imagined reader is. A hardboiled former editor of The Scotsman with a background at the Daily Mail once explained this to me. “Dennis Waterman,” she said, “never gets old.”

So it was 1994. I did interviews for Scotland on Sunday. I had a lot of freedom, which was good and bad. If things worked, it was me. If things went wrong, the same deal.

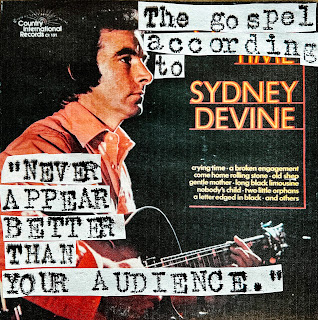

I decided to interview Sydney Devine. These days, Sydney needs a bit of explanation. Perhaps he did in 1994, too. Sydney was, and is, a Scottish country’n’western singer. He was extraordinarily popular. How this came to be is hard to explain, but essentially he was the Woolworth’s Hank Williams, an entertainer who cut his teeth in the working men’s clubs having first come to notice as a talented mimic of bird calls. In his early teens, he appeared on BBC Radio Scotland performing with Ronnie Ronald on the song 'If I Were A Blackbird'. Sydney was the blackbird. At 13, he represented Scotland in a four-nations talent contest called All Your Own, performing live on television at a time when most people didn’t have televisions. He came second to Alex Harvey in a contest to find Scotland’s Tommy Steele.

And so it goes on. Sydney doesn’t earn much, but he keeps performing. In Dundee, he is paid a wage of two packets of chewing gum for a show. He traverses the Central Belt, playing the circuit of old folks’ homes. All of this while he is still at school. Then, at the age of 15, he gets a part in Wild Grows The Heather in London’s West End. It is 1955. £28 a week is a lot. Sydney’s voice breaks halfway through the run. He becomes a light tenor, or, as Sydney likes to say “maybe a fiver”.

The Sydney story really starts around 1969-70, when he tours South Africa with Andy Stewart. (That sentence poses a few questions of its own, but let’s ignore them). Sydney is given some studio time, and records around 20 songs. That’s the moment when the teenage warbler who performed in American Army bases as The Tartan Rocker becomes the Rhinestone Ploughboy, a country entertainer whose arrival in a white spangled jumpsuit ($700 from The Alamo, Nashville) is heralded by a blast of 'Also Sprach Zarathustra', just like Elvis.

Apparently, it happened quite naturally. In the myth, which must be true, a woman (also called Devine, but unrelated) in the Glasgow branch of Woolworth’s takes a liking to Sydney’s album and starts playing it. He becomes a local phenomenon, a big star in a wee picture. “There was Harry Lauder,” Sydney would tell me. “After Harry Lauder came Robert Wilson. After Wilson came [Kenneth] McKellar. After McKellar came Andy Stewart. After Andy Stewart came me.”

So here I am, outside Sydney’s house in Ayr, with a duffel bag full of prejudices. Sydney is, in 1994, a bit of a joke, albeit a joke in which he is complicit. As often as not, he will provide the punchline, though you might - with a bit of sensitivity - detect a note of insecurity in his responses. His appeal, he would tell me, was based on the fact that he was ordinary. Well, “bordering on ordinary”. But consider also that he played guitar on Andy Stewart’s novelty hit ‘Donald Where’s Your Troosers?’ and you get a sense of the unholy mess of cringes and genuflections that are involved in appreciating the divine Sydney, never mind being him.

It’s true. I’ve come to his suburban home in Ayr to laugh. If Sydney wants to play along, all the better. If he doesn’t, well, we’ll see. That’s the game.

Before I get into the house. I notice something strange. There is a squirrel on Sydney Devine’s driveway. It is dead, an ex-rodent, squirrel mortis. I make a mental note. (A symbol of what happened to Sydney’s career after the advent of Daniel O’Donnell, perhaps?) Better use it with care, though. Sydney had retired to run his hotel in 1991 after a heart attack, and un-retired after bypass surgery. When I ask how he is, he replies quickly: “Why? Have you heard something?”

We go into Sydney’s house. It is a nice house, modern and clean. No one else is home, so Sydney repairs to the kitchen to make the coffee. I scan the room for evidence, noting the unending luxury of the deep shagpile carpet. When he returns with the coffee, I clock that it is Nescafe. There is a plate of biscuits. There is something funny about the biscuits, too. I take it all in.

We talk, awkwardly, as if Sydney is aware that he is being set up and is determined to knock himself over first. We talk about singing, and whether Sydney can. “I could sing ‘One Fine Day’ from Madame Butterfly if I thought it would pay the wages,” he says.

“Don’t you sometimes miss the notes?” I suggest, gingerly.

“Miss them?” he retorts. “Intentionally.”

“Why?”

“I maybe just felt like it. The perfect record has never been made.”

He tells me an extraordinary story about the time he went swimming in a river with Jimmy Shand’s son Erskine, who took cramp. “I can swim,” he said, “but I’m not that strong. I’m not a lifeguard.” Erskine swam ahead, so Sydney could help if he got into further difficulties. Halfway across, the cramp struck again, and he slid under the water, pulling Sydney down with him. They were about four feet from the bank. “And for a second, my whole life was there, my mother, all my brothers and sisters, it was incredible.

“It was the most unnerving thing in my whole life. I went under, but how long I was under for I don’t know. How long I was dead for, I don’t know. My whole life, just snap. I could see my family, my wife, my kids, everything there. As if somebody had just gone shhhhh with a paintbrush.”

So here’s the thing about interviews. They are not ordinary conversations. Michael Parkinson says something about them being an exchange between two consenting adults, and that is true to extent, but works better for television, where the to and fro of the conversation is there for all to see. In print, you need to get something. You need material to mould. If you have a nice chat, a nice chat is all you’ll have. If the person is famous, you’ll be thrilled that you got on, but when you transcribe it, there will be nothing there. So interviewing is a process. You may have a checklist. Have I got an intro, an ending, a revelation? (When I stopped working for Scottish newspapers and did some interviewing for London titles, an editor boiled the purpose of an interview down to one question: “What is your guilty secret?”)

So here I am, with Sydney, and I have questioned his singing ability, and he has responded by mentioning the 3.5 million sales of his Crying Time album. His version of the Buck Owens' title song was, he says, “very ordinary. In fact there’s probably nine or ten punters up at Annfield could sing it better, but nobody buys their record.” It would be fanciful to apply science to the success of Sydney Devine. Nevertheless, the singer has a democratic formula which seems to work: “Never appear better than your audience.”

And then it happens. Sydney asks me whether I would like to hear his new album. There is no way to say no, so we move from the drawing room into a narrow annexe, which is decorated with gold discs, a silver salver for breaking the box office record at the Glasgow Pavilion, and a framed portrait of Sydney, the child performer. He has a C90 cassette of his record, and spools through it, trying to find his version of a Neil Sedaka song. And I stand there awkwardly, in very close proximity to Sydney, and I notice something terrible. He smells like shit. It is really bad, and really very awkward. There is nowhere to go in that annexe, so we stand next to each other, saying nothing, breathing in the foul air, as Sydney winds and rewinds the cassette, frantically trying to find the song he likes. The musical bit is awkward enough. How will Sydney cope with a Sedaka number? But the smell is something else.

I’m relieved when Sydney can’t find the song - the quick bursts of ‘Crazy’ are more than enough - and we get out of the confines of the annexe, back into the drawing room, where I spot a framed motto on the wall: “Today is the day you dreamed about yesterday,” it reads, “and all is well.” (Mental note - a good ending). We shake hands and I make my escape down the driveway, past the mortified squirrel, away to the train home.

Interviews are exhilarating, occasionally nauseating, and this encounter has been no exception. So I take a deep breath, and start to think about putting the conversation in some sort of order. I have an ending. Do I have an intro? What did I get? What really happened?

It’s at this point that I cross my legs to rest my notebook on my knee, and the awful smell hits me again. I look down. My shoe is covered in dogshit. Well, not entirely covered. Much of it has surely come off on the deep shag of Sydney Devine’s drawing room carpet, and Sydney, dear old Steak’n’Kidney, has endured, inhaled, and will now have to Hoover away the filth that I have tread through his otherwise spotless house.

I told this story at a journalism awards ceremony. Afterwards, I was accused of making a metaphorical attack on the ethical code of my editor. Perhaps that was my intention. I hope not. Mostly I just wanted to say, in the homespun manner of the Ayrshire Ernest Tubb, be careful of the stones that you throw.

The moral, journalism tip #57: when you smell shit - check your own shoes.

.JPG)

Comments

Post a Comment